Techniques

"Post-Nuclear" Series

The whole thing started as repairs to a broken bowl! One of my finest thin wood vessels had developed cracks due to rough handling, and the remedy was suggested by Hawaii fibre artist Pat Hickman. "Enhance the crack," Pat said. "Give it more character. And burn the edges". I did, and punctured holes so Pat could lace it with her fibre-of-choice ("hog casings") The resultant vessel won an award in its first showing and now is in the permanent collection of the American Craft Museum.

When Pat left the country on sabbatical I continued to explore the concept, but sought even greater contrasts of media. First fine copper wire, then even finer wire, but now in the form of braid. The lacing pattern also evolved, from random appearance in early vessels to a highly stylized cross-pattern on the outside surface of the vessel, and a double straight-across on the inside.

Fuming the entire vessel with vapors of Muriatic acid is the final step, to produce an appealing blue-green patina on the braid.

The series is now over four years old. Its title..."Post-Nuclear" derived from movies that were popular at the time: Waterworld and Thunderdome, both depicting post holocaust societies in which citizens no longer created new artifacts, but rather salvaged broken remnants from scrap-piles and repaired them with even more scrap.

"Post-Nuclear" is no longer merely a method of repair. It is now an intentional enhancement to some of my most precious translucent wood vessels.

Translucent Norfolk Pine

About this display:

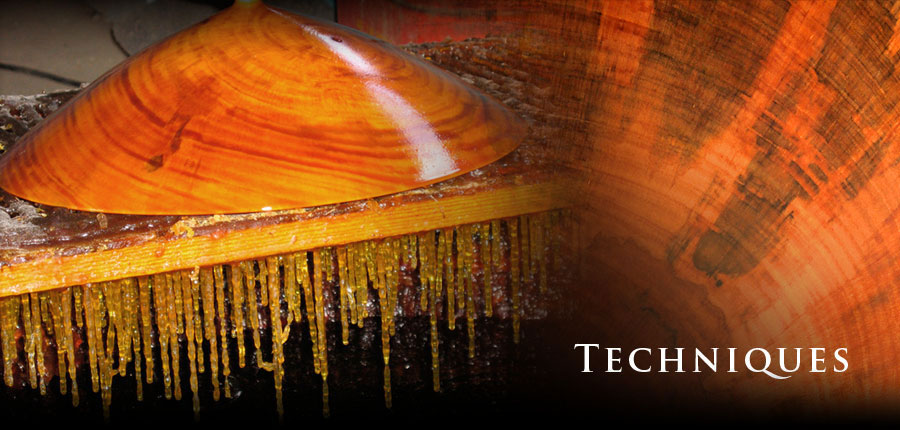

These "oil stalactites" were formed beneath the grill-work upon which my wife and I oil and sandpaper my finished vessels. The grill spans the open top of a 100-gallon vat of Varathane natural Danish-type oil.

My "finishing" process consists of multiple cycles of oil-soak/sandpaper/dry/wait. Typical vessel may undergo as many as fifty such cycles, over a four-to-six month period.

During each cycle the vessel is thoroughly drenched with the tung-type oil, applied with very fine sandpaper. The process is performed on the grating , over the vat, and excess oil drips into the vat for continual reuse. The formations displayed here are created in the same fashion as icicles and rock-stalactites, as each successive dripping leaves an incremental surface film that builds up and hardens.

In these oil stalactites the thin films undergo chemical change (polymerization) and become a tough, flexible plastic-like substance that resists all solvents that I have tried on it. This same substance permeates and becomes integral with the cell-structure of the wood in the finished vessel.

When completed on the lathe, my Norfolk Pine vessels typically range in color from dull ivory to washed-out gray, with a distinctly dry appearance and texture. Upon being dipped into the oil vat they immediately display vivid coloration, sheen, and translucence...which disappears within minutes of removal from the oil. The minuscule amount of oil retained within the wood has no recognizable lasting effect for the first half-dozen applications, but continues to build. The key element of this process is not how long it soaks but how many times, and drying-time is an integral component of the cycle. By the tenth cycle the colors, contrasts, and translucence begin to linger and the ultimate beauty of the wood is displayed.

The gratings I use are old refrigerator-shelves garnered from urban curbside discards, which I replace as they become overly-encrusted with polymerized oil. The section in this display had been in use about eighteen months.

Note: I have used these methods in my own work, as I will describe them, but that work has been with one wood only: Norfolk Island pine, whose unusual porosity and absorbency make it ideally suited for this type of treatment. And only in one woodworking technique, turning on the lathe. I suspect that only minor changes in procedure will yield benefits in many other woods and other processes (sawing, planing, routing, milling), but I leave it to your own curiosity and experimentation, and adaptation to discover if there are any benefits for you.

Experimental New Treatment for Wood

Additional information, and opinions, Google "Ron Kent, Detergent"

Prologue:

"I’ll bet you own a restaurant," said the friendly supermarket check-out clerk.

"No," I replied. "I’m a woodworker".

"A woodworker? Then why..."???

Why, indeed! What does a woodworker do with five gallons of ...but I’m, getting ahead of myself! I will give you the answer to that question. which was only friendly banter at the check-out counter but which may be of interest and use to other craftsmen. I’m going to tell you about a product and procedure that I developed a few months ago and now use as an integral part of every woodturning project. It involves a liquid that I use to soak all my wood, before, during, and after shaping and completing my work on the lathe.

It had a very simple beginning: I bought a gallon of a product that promises to "stabilize and condition" wood. Tried it, liked it. Liked it enough to buy more and to incorporate its use in my daily production. I liked everything about it except the price: nearly fifty dollars per gallon!

I started wondering if there isn’t some other, more common liquid the might do the same job. Something that might soak in, harden, and become part of the wood, bonding the fibers more firmly while also imparting a lubricating quality. It had to be transparent and non-staining. I started my search at the hardware store (Where else?) walking up one row and down the other, scanning each shelf for ideas. Then came the supermarket and the drugstore. One product caught my attention and seemed to hold a lot of hope....Clear acrylic liquid floor-wax! Transparent as water, promising to harden into a tough protective shield. Bonds firmly to the floor so certainly would bond to the wood fibers to form a dense composite. And anyone who has slipped on a newly waxed floor knows wax’s ability to "lubricate."

Tried it, liked it...well, sort of liked it. Acrylic floor wax did indeed meet the criteria I had set up, but in doing so reminded me of another very important characteristic that I had forgotten to consider. Turns out that wax-impregnated wood does not take well to the multiple oil-soak technique I use to enhance translucence. The brilliant golden ambers now looked dusty and dull. And the price of the wax was little better than the conventional product I was hoping to replace. Back to the drawing board!

I tried a number of products over the next few months, haunting again the hardware store, drug-store, supermarket, and giant discount house; trying all sorts of concoctions, individually and in various combinations. In most cases the results were innocuous, in some, downright messy. Till one day, while on a shopping safari with my wife, I noticed her picking up a big bottle of syrupy golden liquid to add to our shopping cart. I made a mental note to give this a try when we got home.

The product? Perhaps it is time to end the suspense. The liquid I tried and now find so useful is...are you ready for this?....concentrated dishwashing detergent: Costco’s Kirkland brand sells for about $7.00/gallon in Hawaii, quite possibly less in other parts of the country. ( My guess is that this is their private label on a similar product with familiar major brand name, and that many or most other brands will deliver the same results.)

What are the benefits that I find? First there is the advantage of stabilizing the wood; a great deal less "moving" and warping both while working on the vessel and after it is taken off the lathe. A second favorable difference shows up in cutting. The shavings are a delight! Clean, long, cohesive ribbons, both for fine trimming and for the macho adversarial plunge-cuts that characterize my favored rough-shaping "technique". It feels almost as if the wood has been lubricated and allows the edge of the tool to slide smoothly through the cut. I never did figure out what "conditioning" means, but whatever it is, I’ll bet detergent does it!

Ah, and on the rare (Hah!!) occasions when I resort to using sandpaper....it is a whole new sanding experience. For one thing it allows sanding work that not only is green, but even wood that is soaking wet. The sandpaper still becomes clogged, mind you, but a couple sharp slaps on the bed of the lathe clears the grit and allows reuse again and again.

And with dry wood...well. you have to try that to see for yourself. The closest I can come to describing the difference is to compare it to certain special woods (ebony comes to mind) where the dust seems to be tiny beads rather than that with which we are more familiar. Again the sense of lubrication.

Technique

Now back to my story. Though the experimentation never ends, I currently use a dilution ratio of one part water to one part concentrated detergent. (I’ve also tried diluting with isopropyl (rubbing) alcohol and suspect I get better penetration, but am not sure it justifies the added expense.) Even after this dilution the result is a viscous, syrup-like liquid, leaving me to suspect that further dilution would heighten the economy without losing effectiveness. I vary the proportion each time I mix it, still seeking an optimum ratio.

I do, however, regularly add eucalyptus oil to the mix. It is available at most drug-stores; I use about one teaspoon per gallon. What does this add to the process? A distinctive, pungent scent It just smells good!

Green wood

All of my work is on logs that I get from local tree-trimmers. They bring it to me as soon as the tree is cut, and I’m likely to start turning it the very next day. The wood at this stage is not only green, it is soaking wet! I strip the bark, mount the log, and rough-turn the shape to about one inch thick. (Attention NASA Engineers: Please read as 2.54 cm.). I remove the work from the lathe and slather on a thick coat of the mix., wait a few minutes for the foam to soak in, then repeat. Maybe as many as a half- dozen times, inside and out.

I haven’t...yet...adapted detergent to my old "trick" of total immersion. (For many years I have used an open vat of Varathane...75 gallons of the stuff...for multiple immersion of completed turnings ). A detergent" pre-soak"----at an early stage of turning---seems the logical next experiment to try. I’m planning a five-gallon tub for starters. (I also have begun experimenting with the mix as a "sealer" on end-grain of cut logs, waiting in my wood-pile. I suspect it will decrease splitting and checking. As for other woods...woods not as porous as Norfolk Pine...well, I’d be very interested in hearing from you if you find out.)

After the soak – by what-ever means – I set the work aside for a few days to allow detergent to permeate the wood, and become surface-dry.

Before I started using detergent this was a chancy thing to do. When I was lucky the vessel-to-be only warped. I wasn’t always lucky. There was a definite risk of losing the work altogether due to checking and cracking. With this new technique my experience to date has been minimal "moving" and zero checking .

At this point I re-mount the workpiece and proceed using the usual tools and procedures, enjoying the benefits to cutting and sanding described earlier.

Dry wood

I use the same procedure on logs that have dried out standing in the wood-pile, and I find the benefits are even more marked. Norfolk Pine dries and spalts very rapidly in Hawaii’s humid climate. Spalting typically starts within a month of the tree’s cutting. By the fourth month the wood is almost completely black. Though there still is considerable moisture in the log, the wood acts as if it were dry. It is significantly more difficult to cut smoothly, and it is easily subject to bruising and tearout. This dark-and-dry wood drinks up detergent like a camel in the desert, but the overall process differs mainly in quantity. My goal is to penetrate...permeate...the wood with liquid detergent. Sometimes I start working the piece right after the soaking, before the detergent has even had a chance to dry. More often, though, I will subject the rought-turned form to repeated soakings over a period of days, then allow up to two weeks of standing before I finish the piece. Did I mentioned "conditioning" and "stabilizing? Let me now add another word of description: This wood acts as if it has been rejuvinated.

Effect on Finish

I told you about trying acrylic wax and rejecting it because of its effect on the final finishing process. Detergent, on the other hand, seems to actually enhance my own particular technique. Remember: my finishing process consists of multiple cycles of soak, oil-sand, and dry. The detergent-treated vessel is fully receptive to absorbtion of the oil. It is difficult for me to be certain, but it seems to me that I am achieving even more dramatic translucence from the oils when using wood that was treated with detergent during forming of the vessel. How will detergent affect other finishing techniques on other woods? I haven’t tried it, so I do not know, but my strong expectation is that, once dry, the detergent-treated wood will accept any of our standard, traditional finishes and that it might greatly improve cohesion of the new water-based products.

Safety

We woodworkers should always be conscious of safety in our work....personal as well as environmental (my membership card in American Association of Woodturners arrives in the mail with a Dayglo checklist of cautions). Our workshops are virtual minefields of chemical, mechanical, and biological hazards. The concentrated liquid dishwashing detergent, however, seems quite benign. The bottles carry only a mild word of caution: " In case of eye contact rinse thoroughly with water", and "if swallowed (swallowed??) drink a glass of water to dilute. Contact a physician." Oh, yes, "To avoid irritating fumes do not mix with chlorine bleach." The label also boasts that it is "specially formulated to kill germs on hands when used as a handsoap, contains no phosphorus, and has biodegradable cleaning agents." It even is "Safe for septic tanks"....though that doesn’t happen to be one of my own concerns. Note: No mention of use as a wood conditioner or stabilizer. I think it is a safe bet that the manufacturer never envisioned this usage and it behooves us to make our own list of common-sense cautions. Primary among these is dust protection. I’m no more anxious to breathe detergent-treated dust than I am any other kind. Everything I’ve described in this article is still (may always be) in the experimental stage, with more questions than answers. "Benign?" Maybe, but I strongly urge everyone to use all of the normal precautions that accompany good practice in the shop.

The Soap Solution

Leif O. Thorvaldson, Eatonville, WA

Having a reawakening to the pleasures of woodturning after a gap of four years, I plunged into it with enthusiasm. Buying books and videos and eagerly visiting every site, both personal and commercial. I became increasingly discomfited by what I read and learned. Experienced turners and professional turners were constantly carrying on about multitudinous ways of "drying" wood so as to avoid cracking. One way in particular had my hasty heart dismayed when it was described that one should rough turn the wood, slather it up with various lotions and potions and let it sit for six months to six years. One was to build an enormous pile of these objects by constantly adding to the drying rack and, at the end of the six months (or six years), check to see if the roughed out blank had cracked or warped so badly as to be unusable. If not, one could then turn it to completion, finish it and hope that it wouldn't crack thereafter. Faster methods were suggested: boiling, microwaving, burying in manure piles, compost heaps, sawdust piles, storing in sealed plastic bags, unsealed plastic bags, dry paper bags, wet paper bags, immersing or spraying with WD-40, ad nauseum. None of these did what I wanted to do, i.e., pickup a piece of green wood, turn it, sand it and finish it within a day or two without unsightly cracks occurring.

One fateful day, browsing on my computer while waiting for the first six months to elapse, I encountered a very lovely website by Ron Kent (https://www.ronkent.com). He had some beautiful Norfolk Pine turnings -- very thin -- and used some unique finishing techniques. All very nice, but what struck me was a technique he had developed for stabilizing and conditioning wood. He had tried the expensive route, but was looking for something under $50 per gallon. To make his story short, he found that Costco's house brand (Kirkland) liquid dishwashing detergent mixed with an equal amount of water provided hitherto unavailable qualities in both conditioning and stabilizing of wood for almost immediate turning and finishing

I went to Costco and purchased four half gallon containers of the magic elixir along with a sturdy plastic storage bin of sufficient size to hold the mixture and some bowl blanks. Upon arrival at home, I emptied the detergent into the container and added an equal amount of water. From then on, I would take primarily green wood and rough turn in one day, soak overnight, and finish the next day. Sometimes I didn't finish it on the second day and left it mounted on the lathe overnight and sometimes for a several days. Surprise! They didn't crack! I have since taken green wood, rough turned it, soaked it about four hours and then finish turned it and finished it in one day. In the six to eight months I have been using this technique, I haven't had one bowl crack. A few had a bit of movement, but it was very slight. I have used the following woods: black walnut, vine maple, maple, oak (kiln dried), yew, honey locust, fruiting cherry, birch, plum, apple. I have not tried madrona as I refuse to cut down the only one I have growing on my property.

Needless to say, I was ecstatic and proceeded to share my "discovery" with any and all turners I knew (two) and also spread the word on rec.crafts.woodturning (a regular not-so-little Johnny Appleseed I was!). A few turners were lured into trying it. Unfortunately, some people can't follow directions and tried variations on the simple recipe which resulted in cracking. A few did it correctly and were rewarded with success.

There has been some speculation as to the mechanism behind the process, but no real scientific investigation has been done. Lyn Mangiameli, John Nicklin and I have come up with the following theory which John set to words

'The soap solution sets up an osmotic gradient. Pure water in the wood is in more abundance than water in the soap solution, so it (the water) tries to migrate to balance the osmotic pressure. This would cause the specific gravity of the soap solution to decrease (although possibly not noticeably.) On the other hand, the concentration of soapy stuff is higher outside the wood than in, so it tries to migrate into the wood. If it is successful in

migrating into the cells, the soapy solids will get trapped as the wood dries, preventing the cells from collapsing as they do when wood dries naturally (or unnaturally for that matter.)

As you point out, the soap solution is slicker than a Teflon banana peel This may help the migration of soapy solids into the cells."

An attempt was made by Lyn to conduct a survey to gather details for a study on the detergent/soap technique. Unfortunately, he received only 11 responses from turners, so feels that no meaningful statement can be made as to the efficacy of the process.

The only slight drawback to the detergent solution is that the wood should be drained for a few minutes or longer and wiped with a towel while mounting it to the headstock. A plastic sheet should be placed over the ways and eye protection should be worn. Try it! Your hands will be smoother, cleaner and less subject to cracking as well as your turnings.

Selected Permanent Collections

21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art

Kanazawa, Japan

The Louvre

(Musée des Arts Decoratifs)

Paris

det Danske Kunstindustrimusee

Copenhagen

Hawke's Bay Cultural Trust

Hawke's Bay, New Zealand

The White House

Permanent Collection

Washington D.C.

Smithsonian American

Art Museum (SAAM)

Washington, D.C.

Victoria and Albert Museum

London

Cooper-Hewitt

National Design Museum

New York

Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York

Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Minneapolis

Museum of Art + Design

New York

Museum of Fine Arts

Boston

Yale University Art Gallery

Newark

Mobile Museum of Art

Alabama

Mint Museum of Art + Design

Charlotte, NC

High Museum of Art

Atlanta

The Detroit Institute of Arts

Detroit

Carnegie Museum of Art

Pittsburgh

Arizona State University

Tempe

Los Angeles County

Museum of Art

Los Angeles

Selected Special Presentations

Dr. Thomas Klestil

President, Republic of Austria

by J. Hans Strasser,

Consul General of Austria in Hawai'i

1995

Emperor Akihito of Japan

by Kensaku Hogen,

Consul General of Japan in Hawai'i,

and the Japan-America Society

1993

President William Jefferson Clinton,

by Congressman Neil Abercrombie

1993

President George Bush

by Congresswoman Patricia Saiki

1990

His Holiness Pope John Paul II

by Drs. Roger and Maria Brault

1987

Crown Prince Hitachi of Japan

by the Hawaiian Japanese Chamber of

Commerce

1985

Senator Daniel Inouye,

by Hawaii Democrat Party H.R.H.

1985

Sultan Iskandar of Johor,

Agong of Malaysia

(Personal purchase)

1985

President Ronald Reagan,

by Hawaii Republican Party

1984

Supreme Court Justice

William Brennan,

by the University of Hawai'i

School of Law

1983

Governor Hikaru Kamei,

Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan,

by the Hawaii State Senate

1981

Selected Traveling Exhibits

Smithsonian Institution

Traveling Exhibition

USA, New Zealand

Craft Today

USA, Europe

International Turned Objects Show

USA, Canada

Out of the Woods

FAMOS, Eurpoe